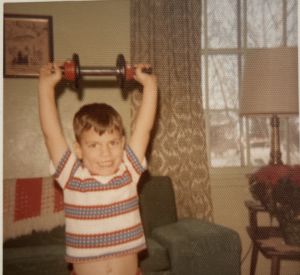

I was first introduced on a high level to goal setting in my early teens when I was encouraged to start powerlifting to overcome some health issues. My brother was the primary motivator, and on day one, goals were set. I had daily goals, monthly goals, and overall goals for every lift, every set, every aspect of training. Without them, progress would have been slow, and things would have been forgotten. The adage of writing the goal down was evident and needed. Why? Mainly because there was so much information, writing down things were required to keep things organized and tracked.

I was first introduced on a high level to goal setting in my early teens when I was encouraged to start powerlifting to overcome some health issues. My brother was the primary motivator, and on day one, goals were set. I had daily goals, monthly goals, and overall goals for every lift, every set, every aspect of training. Without them, progress would have been slow, and things would have been forgotten. The adage of writing the goal down was evident and needed. Why? Mainly because there was so much information, writing down things were required to keep things organized and tracked.

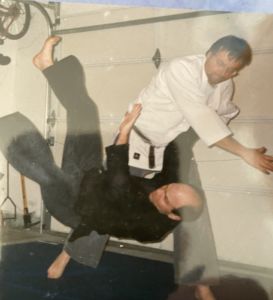

I started martial arts soon after and found out that goals were inherent in karate and jujitsu training. Kata, throws, advancement all had small goals, and big goals needed to progress.

The following are some things that I learned from these two processes that I wanted to share.

Thoughts on goals, from a lifelong martial artist and reformed powerlifter:

By Charles Orchard

I think sometimes I give the impression that I hate goals, but my true feelings couldn’t be more opposite. Goals are essential to our improvement and progress in life. What I do hate is setting a goal, doing the work to get there, and then having it all be for naught because I never approach that goal again. If I’m going to put the work in, I want to know I’m getting some kind of long-term benefit—I don’t want to just be able to say I did something once. I hope to encourage you to set high-quality goals toward improving yourself, and to help you consider how engaging in marital arts training can build this mindset.

Japanese culture encourages continuous improvement and skill integration. I think that philosophy is at the root of my own thinking—which makes sense, given my long practice in karate and jujitsu. When I was born, I had a disability that prevented some development; I also had health issues as a young child. By the time I was a preteen, I’d mostly caught up to my benchmarks. But I still needed some help, so my (twelve years older) brother asked my mom and dad if he could start me in karate and weightlifting and they said of course. After lifting for a few months, my brother set a goal for me to compete in a high school meet. I was apprehensiv e, but agreed, and ended up getting third place in my weight class after having started only six months earlier.

e, but agreed, and ended up getting third place in my weight class after having started only six months earlier.

That achievement was the result of training with a clear goal in mind. It’s the process and training that are important, even though that early win felt good on its own. I had many competitions after that first one: I won some, placed in all of them, and always focused on how the process was changing me for the better. The immediate result is momentary, fleeting pride, but the learning and growth stay with me today: I still lift, I still work to improve, and I’m much older than when I started.

This mindset is vital to karate, jujitsu, and other martial arts. Belts are tangible goals built into the training, showing how a martial artist is advancing. Belts were important to me, as they should be to every teenager learning these arts, but my method was to focus on developing knowledge and understanding technique. These training methods shaped my approach to problem solving, my career, my studies, and many other aspects of my life. Attempting challenges just for the trophy or recognition, all but ignoring the process and its larger impacts, is what I call a vanity or bragging-rights goal—these have their place, but it’s important to make sure they’re secondary to process development goals. If I were doing karate and powerlifting just for the short-term thrill of winning competitions or getting my next belt, I wouldn’t probably still be involved.

How do you set a life process goal?

The first step is to pick something you’ll enjoy, whether that’s running a marathon or competing in ballroom dance—whatever speaks to your interest. Then, think about the process and the schedule you’ll need to keep in order to achieve your goal. Keep breaking those big steps down into smaller pieces that you can achieve along the way: maybe you set a goal to run three times a week for the first stage and aim to increase your distance over time. Maybe your small goals are practicing, training, reading, or increasing your limits every day. For powerlifting, we would set weekly improvement goals on lifts; for karate and jujitsu, small goals might be mastering a particular throw or movement within a set time frame. This process works for everything you might att empt. Make a schedule and set goals for each scheduled session, starting with one or two or a few simple goals to build on for the length of time needed to reach your end result.

empt. Make a schedule and set goals for each scheduled session, starting with one or two or a few simple goals to build on for the length of time needed to reach your end result.

Once you’ve set your end goal, your schedule, and your benchmarks, look at your process and try to identify what it does for you beyond the trophy you’re going to put on a shelf. What did it give you? What did you learn from it? It’s sad for a runner to successfully run in a marathon and then never run again; it’s a waste for a martial artist to put on their black belt for the first time and then never set foot on another mat. You don’t have to keep running marathons or keep seeking advanced belts, but running or practicing regularly will help you keep the larger benefits of good health

and endurance you gained along the way.

But Charles, you

say, if you’re not at your peak you lose what you’ve gained. I know: it’s going to feel like a step back if you’re not still at the top of your game. But it’s also important to recognize that most of us function best at the middle of the curve over a longer period, since being at the top can work to limit us in the long run. What’s important is to maintain the habits, the physical benefits, and the opportunities we give ourselves through the process of improvement. And those are just the most visible benefits: a marathon runner also usually learns about nutritional needs, a jujitsu black belt learns about spatial awareness and operational physics, a karate artist learns self-awareness and how to manage tense situations. Is it a good idea to stop eating healthy? To move through the world without being aware of your surroundings? Why not use the knowledge you’ve gained to improve your whole life?

It’s not enough to keep using your new skills and knowledge only to keep achieving goals like the one you initially set, though you can certainly keep signing up for marathons or mastering new karate katas. Almost every goal has steps in the process that will improve our lives in some way, if we continue to use them. Even something more isolated like skydiving can improve your life in the long run: even if you never jump out of another plane because you were so scared the first time, you’ve learned greater courage and follow through by doing something that scared you. This is the beauty of this mindset, that even small steps repeated consistently can significantly improve our lives.

Set goals. Achieve goals. And as you learn to improve toward your specific outcome, also learn how to improve yourself and the rest of your life